Go offline with the Player FM app!

For One Vietnamese Family in LA, This Broth Is Rich With Memories of Life After War

Manage episode 483221318 series 3516123

Standing over a gas burner in his outdoor kitchen in South Pasadena, Hong Pham toasted an onion and a whole ginger root until they were smoky and black.

Every Vietnamese household needs a kitchen in their backyard or garage to do the “smelly cooking,” he joked, emphasizing that charring the aromatics is key to enhancing the flavor of miến gà, a Vietnamese chicken and glass noodle soup.

The dish is comfort in a bowl — and special to Hong and his family, who are among the diaspora of people who fled Vietnam after the war ended a half century ago and settled in places like California. Miến gà was one of the first homemade meals his family had together after reuniting at a refugee camp.

I had a miserable cold this winter and was searching for a recipe for miến gà when I found one posted by Hong and his wife, Kim Dao, on The Ravenous Couple, their popular food blog, YouTube videos and Instagram account.

Alongside the recipe, Hong shares a story his father, Tung, told him about the soup’s connection to April 30, the day Saigon fell to communist forces, and his life began to unravel.

Because he had served in the South Vietnamese Army, Tung was sent to a Viet Cong re-education camp as punishment for supporting the Americans’ war effort. He endured three years of starvation and hard labor, separated from his family.

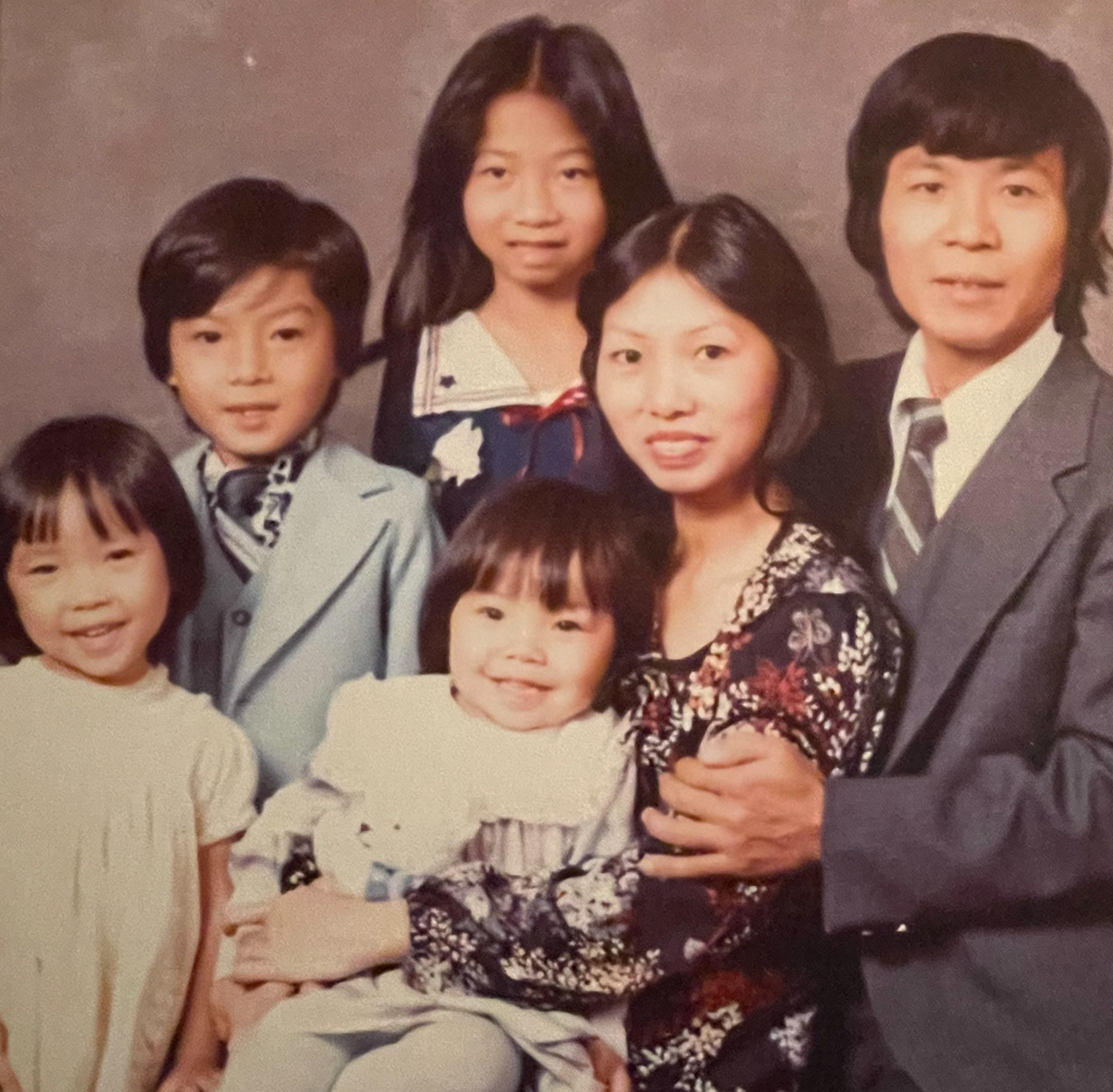

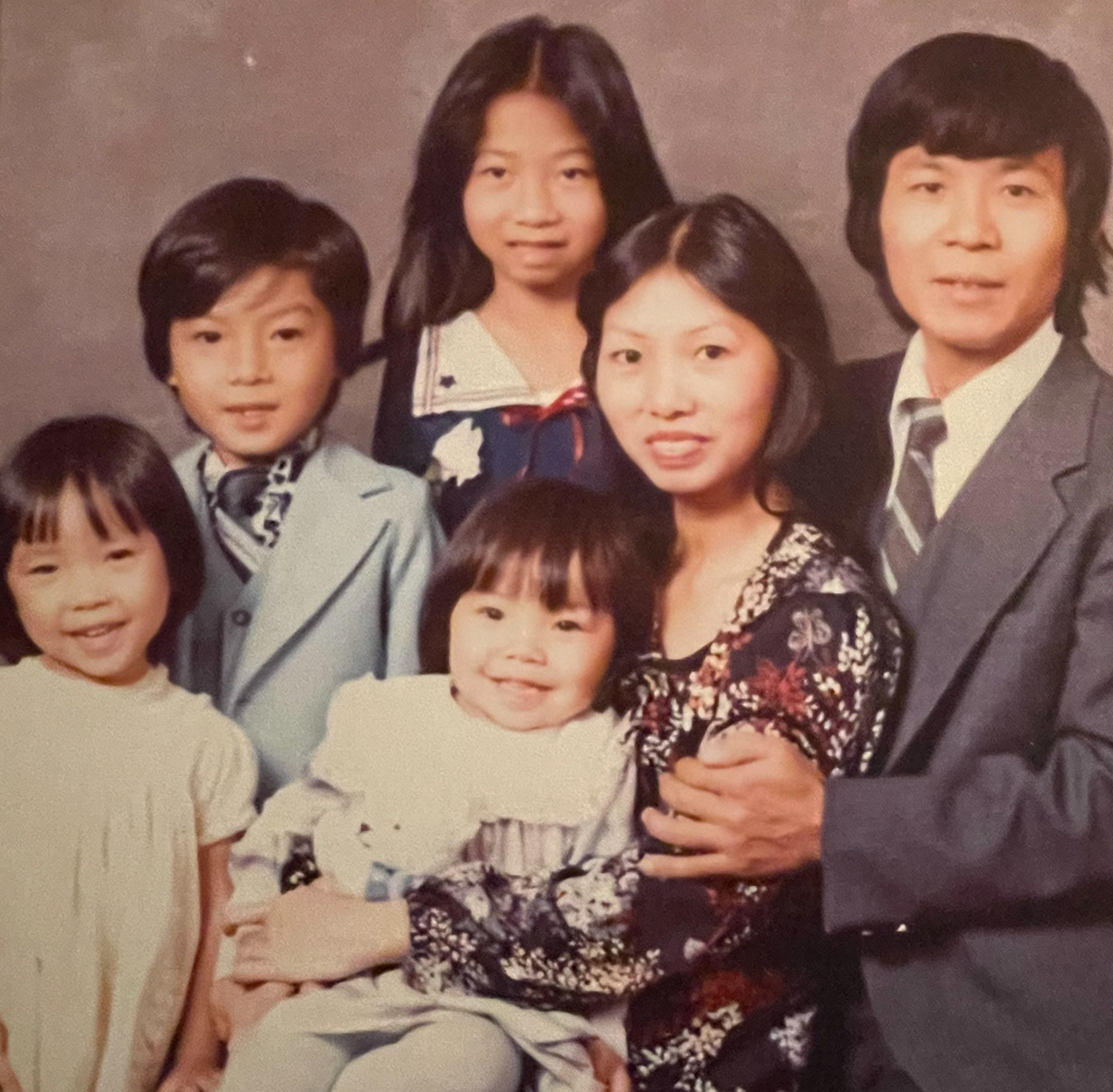

When he got out, Tung tried to make a living as a teacher, but he barely scraped by. In March 1980, he decided to escape, joining the exodus of Vietnamese refugees who fled their homeland by boat. Because he could only afford three spots on an overcrowded fishing boat, Tung took his two eldest kids — Hong, who was almost 6 at the time, and his 9-year-old sister, Tam — and left behind his pregnant wife, Ly, and another daughter, Hong Ngoc, who was barely 2.

“My mom and dad were OK with splitting up the family, even though they had no idea when — how — at what point in the future, if ever, they would see each other again,” Hong said. “For them to make that decision [when they were] in their 30s was unimaginable to me.”

Hong and Kim started their blog 16 years ago when they were still dating. They were craving Vietnamese food and wanted to learn how to recreate the dishes their moms cooked for them. Hong’s mom cooked intuitively, using everyday kitchen tools like rice bowls to measure her ingredients, so he decided to write down her methods so he could follow her recipes precisely. Kim helped convert the amounts into the American system of cooking measurements.[aside postID=news_12037680 hero='https://cdn.kqed.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2025/04/20240403_BETTYDUONG_GC-12-KQED-1020x680.jpg']This drew Hong closer to his mom, especially after he moved away from home in Michigan, where the family resettled after coming to America. He often calls her when he’s cooking to get her advice.

When he went to college and came home to visit during breaks, his mom often greeted him by asking, “Have you eaten?”

“I would just answer her yes or no, and didn’t think much about it. But now, as a parent, I know what she really meant. It was her way of nourishing us and showing her love and affection,” he said. “And so now that we both cook, we’re so much tighter because of our cooking.”

As a daughter of Vietnamese immigrants, I can relate. My parents, brother and I traveled by plane to the United States in 1984 as part of a later wave of refugees who were admitted to the country under the Orderly Departure Program.

Whenever we call each other, my parents always first ask, “Have you eaten?”

I had been a longtime admirer of The Ravenous Couple and their culinary adventures. After finding the recipe for miến gà and reading his dad’s story, I reached out to Hong. He was as open and friendly as he seemed online, and he invited me to come cook with him.

We moved from his backyard kitchen to his brightly lit indoor kitchen to continue making the soup. Hong called his mom on FaceTime at her home in suburban Detroit to ask how much dry bean thread noodles to use in the dish, because they quickly expand in water. I asked her to share her memories of her family’s flight from Vietnam.

Ly said in Vietnamese that after Tung left, she waited anxiously for news. Tung and the children went on a boat led by the same smuggling organization her other family members hired to get to a safer shore. The group was reputable, but there were reasons to worry: The journey was dangerous and an untold number of refugees lost their lives to dehydration, starvation, pirate attacks or rough seas.

About 10 days later, a man working for the leader of the smuggling operation came to her door. He said that during the journey to Thailand, Tung begged the leader to bring his wife and toddler on the next trip out of Vietnam, and he agreed.[aside postID=news_12037891 hero='https://cdn.kqed.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2025/04/Paris-By-Night-Ilo_3-1020x659.jpg']Ly said she couldn’t afford to go, but the man urged her to quickly come up with a payment and leave while she was still five months pregnant.

“He told me if I refused to go, it was my fault because [the ringleader] was trying to keep his promise to my husband,” she said.

With her mom’s help, Ly borrowed enough gold — the most desirable currency in post-war Vietnam — from neighbors and friends to board a boat with about 90 other refugees, with Hong Ngoc on her lap.

Ly said the sea was calm and the boat was so overloaded that she could stretch her arm and touch the water. They quickly ran out of food and water, so she fed her daughter a citrus syrup she had made for the trip, so she wouldn’t cry from thirst and hunger.

They traveled for three days and two nights before landing on an island near the Thai-Cambodian border. Ly said authorities eventually transported her group to a refugee camp in Laem Sing, a district in eastern Thailand. She and Hong Ngoc arrived on April 30, 1980, five years after the Fall of Saigon. She recalled seeing Tung, Hong and Tam in the crowd of people rushing to welcome the latest load of survivors.

“We were so overcome with emotions, we just hugged each other and cried,” she said.

Vietnamese refugees consider April 30 a day of mourning. They call it “Black April” because it was the day they lost their country. But for the Phams, it was also a day of rebirth.

“So many people were lost at sea … so for our family to be able to reunite like that was really a miracle,” Hong said.

Because of the secrecy surrounding the escape, they never learned the name of the smuggling operation’s leader. He was only known as “Anh Bo.” Hong and his sister, Tam, said they wish they could thank him for bringing their family together.

“He could have taken anybody, but he kept his word. Even to this day, that means a lot,” Tam said by phone from her home outside Detroit.

Once reunited, the family stayed in Thailand for several more months so Ly could give birth. Tung named their new baby girl Tudo, or tự do, which means freedom in Vietnamese.

At the refugee camp, the family received daily rations of food. Ly said one day, each person received a piece of chicken, so she put everyone’s portion together to make miến gà.

In the blog, Tung described feeling grateful to eat miến gà with his family, reunited and free.

“Thinking what could have been and the remote odds of seeing my family together so soon, I ate this simple dish with such happiness,” he said. “It was the most satisfying and unforgettable meal I’ve ever experienced.”

Ly said she was thankful to her brother, who was the first in her family to arrive in the United States, for sending the money to the refugee camp so she could buy the noodles and other ingredients for the soup.

At home in South Pasadena, Hong used a whole chicken — head and feet intact — he bought from a fresh poultry store to make his version of miến gà. He placed the chicken in a boiling pot of broth, threw in the charred onion and ginger and reduced the stock to a simmer. Once the chicken was cooked, about 30 minutes later, he lifted it out of the pot and submerged it in a bowl of ice water.

Next, he placed the translucent noodles into a handmade ceramic bowl, ladled in the broth and seasoned it with pungent fish sauce. He garnished the soup with chicken, shiitake mushrooms, fried shallots, scallions and fresh chives picked from his herb garden.

He said his mom used to scoff at his precise plating technique and his insistence on pairing certain dishes with ceramic pieces that he made — a hobby he picked up during the pandemic — to make sure they “look pretty for the ‘Gram.”

It’s a generational difference, Hong said, because his mom had to cook for survival, whereas he has the luxury of consuming food “with more intention.” We gathered around his dining table and slurped miến gà with Hong’s daughters, Mira and Emi. The noodles were slippery and the soup had an intense chicken flavor combined with the umami of shiitake mushrooms.

After Tudo was born, the Phams were admitted to the United States as refugees and resettled in Michigan with the support of a Catholic charity. They rented a house in suburban Detroit. Tung worked as a janitor and assembled machinery parts at a factory, while Ly stayed home.

“When I came here, I didn’t know one word of English, and I didn’t know how to drive. I didn’t know anything,” she said. “But I tried to raise my kids and teach them Vietnamese so they wouldn’t lose their cultural heritage.”

When the children went to school full-time, she went back to work as a butcher, a trade she did in the wet markets of Vietnam, this time at a Jewish deli. She also volunteered at her Catholic church, often by making and selling Vietnamese food to raise money for various causes.

“My children didn’t understand why I spent so much time in church,” she said. “I explained that before we left, I prayed to God that if He delivers our family to safety, I would do everything I could to serve my faith.”

The family started over with almost nothing.

Hong remembers wearing secondhand clothes for years because his parents were saving money to pay back their debt. For their first Christmas, his parents wrapped empty boxes and put them under a donated tree because they couldn’t afford to buy gifts.

“My mom mentioned that when we first arrived, the [sponsor] families didn’t know what we liked to eat and so they would give us canned peas, canned corn and things like that — and a lot of mashed potato flakes and macaroni and cheese,” Hong said.

She didn’t know how to cook any of it, and instead used whatever she could find at American supermarkets to recreate Vietnamese food.

“I think that was the ingenuity of that generation. She used all these American ingredients, but it was all made in a Vietnamese way,” he said.

Along the way, small acts of kindness helped the family survive.

When someone noticed that Tung was taking the bus to get from one job to another, they offered him rides. Later, a sponsor gave him a used car and taught him to drive.

“It was a collective effort, a lot of generous people in the community helped us get through a tough time,” Hong said.

Hong said his parents constantly reminded him and his siblings how lucky they were to be in the land of opportunity and achieve their dreams. The four kids graduated from the University of Michigan and went on to earn graduate degrees. Hong became a doctor, Tam an engineer, Ngoc a public health expert, and Tudo an attorney.

Though he lives far away from his parents, Hong and his wife stay connected to their heritage by speaking Vietnamese to their daughters and by sharing food with their community. They host cooking parties in their backyard to help raise funds for charities. More recently, they made an inventive version of banh mi with brisket and homemade pickles to support victims of the Eaton wildfire in nearby Altadena.

Hong said Tung is 85 and no longer able to speak coherently due to a stroke. Ly takes care of him. Hong said he’s glad he recorded Tung’s memories of miến gà years ago and regrets not doing more recordings while his dad was still able to speak. He said his dad was a great storyteller and had a knack for spotting Vietnam veterans wherever they went.

“He’d approach them really casually and thank them for their service, and next thing you know, they’ll have a long conversation,” Hong said. “He loved to share his stories and listen to other people’s stories as well.”

If his dad could speak, Hong said he would probably say that he’s “forever grateful to America for welcoming us as a family and as a whole community.”

He said he also thinks Tung would be sad about the country’s tough immigration policies under President Donald Trump.

“Part of me also would like to think he would be abhorrent about the current state of America, the freedoms that he escaped and risked his life and lives of his children for, slowly eroding away,” he said.

[ad floatright]

101 episodes

Manage episode 483221318 series 3516123

Standing over a gas burner in his outdoor kitchen in South Pasadena, Hong Pham toasted an onion and a whole ginger root until they were smoky and black.

Every Vietnamese household needs a kitchen in their backyard or garage to do the “smelly cooking,” he joked, emphasizing that charring the aromatics is key to enhancing the flavor of miến gà, a Vietnamese chicken and glass noodle soup.

The dish is comfort in a bowl — and special to Hong and his family, who are among the diaspora of people who fled Vietnam after the war ended a half century ago and settled in places like California. Miến gà was one of the first homemade meals his family had together after reuniting at a refugee camp.

I had a miserable cold this winter and was searching for a recipe for miến gà when I found one posted by Hong and his wife, Kim Dao, on The Ravenous Couple, their popular food blog, YouTube videos and Instagram account.

Alongside the recipe, Hong shares a story his father, Tung, told him about the soup’s connection to April 30, the day Saigon fell to communist forces, and his life began to unravel.

Because he had served in the South Vietnamese Army, Tung was sent to a Viet Cong re-education camp as punishment for supporting the Americans’ war effort. He endured three years of starvation and hard labor, separated from his family.

When he got out, Tung tried to make a living as a teacher, but he barely scraped by. In March 1980, he decided to escape, joining the exodus of Vietnamese refugees who fled their homeland by boat. Because he could only afford three spots on an overcrowded fishing boat, Tung took his two eldest kids — Hong, who was almost 6 at the time, and his 9-year-old sister, Tam — and left behind his pregnant wife, Ly, and another daughter, Hong Ngoc, who was barely 2.

“My mom and dad were OK with splitting up the family, even though they had no idea when — how — at what point in the future, if ever, they would see each other again,” Hong said. “For them to make that decision [when they were] in their 30s was unimaginable to me.”

Hong and Kim started their blog 16 years ago when they were still dating. They were craving Vietnamese food and wanted to learn how to recreate the dishes their moms cooked for them. Hong’s mom cooked intuitively, using everyday kitchen tools like rice bowls to measure her ingredients, so he decided to write down her methods so he could follow her recipes precisely. Kim helped convert the amounts into the American system of cooking measurements.[aside postID=news_12037680 hero='https://cdn.kqed.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2025/04/20240403_BETTYDUONG_GC-12-KQED-1020x680.jpg']This drew Hong closer to his mom, especially after he moved away from home in Michigan, where the family resettled after coming to America. He often calls her when he’s cooking to get her advice.

When he went to college and came home to visit during breaks, his mom often greeted him by asking, “Have you eaten?”

“I would just answer her yes or no, and didn’t think much about it. But now, as a parent, I know what she really meant. It was her way of nourishing us and showing her love and affection,” he said. “And so now that we both cook, we’re so much tighter because of our cooking.”

As a daughter of Vietnamese immigrants, I can relate. My parents, brother and I traveled by plane to the United States in 1984 as part of a later wave of refugees who were admitted to the country under the Orderly Departure Program.

Whenever we call each other, my parents always first ask, “Have you eaten?”

I had been a longtime admirer of The Ravenous Couple and their culinary adventures. After finding the recipe for miến gà and reading his dad’s story, I reached out to Hong. He was as open and friendly as he seemed online, and he invited me to come cook with him.

We moved from his backyard kitchen to his brightly lit indoor kitchen to continue making the soup. Hong called his mom on FaceTime at her home in suburban Detroit to ask how much dry bean thread noodles to use in the dish, because they quickly expand in water. I asked her to share her memories of her family’s flight from Vietnam.

Ly said in Vietnamese that after Tung left, she waited anxiously for news. Tung and the children went on a boat led by the same smuggling organization her other family members hired to get to a safer shore. The group was reputable, but there were reasons to worry: The journey was dangerous and an untold number of refugees lost their lives to dehydration, starvation, pirate attacks or rough seas.

About 10 days later, a man working for the leader of the smuggling operation came to her door. He said that during the journey to Thailand, Tung begged the leader to bring his wife and toddler on the next trip out of Vietnam, and he agreed.[aside postID=news_12037891 hero='https://cdn.kqed.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2025/04/Paris-By-Night-Ilo_3-1020x659.jpg']Ly said she couldn’t afford to go, but the man urged her to quickly come up with a payment and leave while she was still five months pregnant.

“He told me if I refused to go, it was my fault because [the ringleader] was trying to keep his promise to my husband,” she said.

With her mom’s help, Ly borrowed enough gold — the most desirable currency in post-war Vietnam — from neighbors and friends to board a boat with about 90 other refugees, with Hong Ngoc on her lap.

Ly said the sea was calm and the boat was so overloaded that she could stretch her arm and touch the water. They quickly ran out of food and water, so she fed her daughter a citrus syrup she had made for the trip, so she wouldn’t cry from thirst and hunger.

They traveled for three days and two nights before landing on an island near the Thai-Cambodian border. Ly said authorities eventually transported her group to a refugee camp in Laem Sing, a district in eastern Thailand. She and Hong Ngoc arrived on April 30, 1980, five years after the Fall of Saigon. She recalled seeing Tung, Hong and Tam in the crowd of people rushing to welcome the latest load of survivors.

“We were so overcome with emotions, we just hugged each other and cried,” she said.

Vietnamese refugees consider April 30 a day of mourning. They call it “Black April” because it was the day they lost their country. But for the Phams, it was also a day of rebirth.

“So many people were lost at sea … so for our family to be able to reunite like that was really a miracle,” Hong said.

Because of the secrecy surrounding the escape, they never learned the name of the smuggling operation’s leader. He was only known as “Anh Bo.” Hong and his sister, Tam, said they wish they could thank him for bringing their family together.

“He could have taken anybody, but he kept his word. Even to this day, that means a lot,” Tam said by phone from her home outside Detroit.

Once reunited, the family stayed in Thailand for several more months so Ly could give birth. Tung named their new baby girl Tudo, or tự do, which means freedom in Vietnamese.

At the refugee camp, the family received daily rations of food. Ly said one day, each person received a piece of chicken, so she put everyone’s portion together to make miến gà.

In the blog, Tung described feeling grateful to eat miến gà with his family, reunited and free.

“Thinking what could have been and the remote odds of seeing my family together so soon, I ate this simple dish with such happiness,” he said. “It was the most satisfying and unforgettable meal I’ve ever experienced.”

Ly said she was thankful to her brother, who was the first in her family to arrive in the United States, for sending the money to the refugee camp so she could buy the noodles and other ingredients for the soup.

At home in South Pasadena, Hong used a whole chicken — head and feet intact — he bought from a fresh poultry store to make his version of miến gà. He placed the chicken in a boiling pot of broth, threw in the charred onion and ginger and reduced the stock to a simmer. Once the chicken was cooked, about 30 minutes later, he lifted it out of the pot and submerged it in a bowl of ice water.

Next, he placed the translucent noodles into a handmade ceramic bowl, ladled in the broth and seasoned it with pungent fish sauce. He garnished the soup with chicken, shiitake mushrooms, fried shallots, scallions and fresh chives picked from his herb garden.

He said his mom used to scoff at his precise plating technique and his insistence on pairing certain dishes with ceramic pieces that he made — a hobby he picked up during the pandemic — to make sure they “look pretty for the ‘Gram.”

It’s a generational difference, Hong said, because his mom had to cook for survival, whereas he has the luxury of consuming food “with more intention.” We gathered around his dining table and slurped miến gà with Hong’s daughters, Mira and Emi. The noodles were slippery and the soup had an intense chicken flavor combined with the umami of shiitake mushrooms.

After Tudo was born, the Phams were admitted to the United States as refugees and resettled in Michigan with the support of a Catholic charity. They rented a house in suburban Detroit. Tung worked as a janitor and assembled machinery parts at a factory, while Ly stayed home.

“When I came here, I didn’t know one word of English, and I didn’t know how to drive. I didn’t know anything,” she said. “But I tried to raise my kids and teach them Vietnamese so they wouldn’t lose their cultural heritage.”

When the children went to school full-time, she went back to work as a butcher, a trade she did in the wet markets of Vietnam, this time at a Jewish deli. She also volunteered at her Catholic church, often by making and selling Vietnamese food to raise money for various causes.

“My children didn’t understand why I spent so much time in church,” she said. “I explained that before we left, I prayed to God that if He delivers our family to safety, I would do everything I could to serve my faith.”

The family started over with almost nothing.

Hong remembers wearing secondhand clothes for years because his parents were saving money to pay back their debt. For their first Christmas, his parents wrapped empty boxes and put them under a donated tree because they couldn’t afford to buy gifts.

“My mom mentioned that when we first arrived, the [sponsor] families didn’t know what we liked to eat and so they would give us canned peas, canned corn and things like that — and a lot of mashed potato flakes and macaroni and cheese,” Hong said.

She didn’t know how to cook any of it, and instead used whatever she could find at American supermarkets to recreate Vietnamese food.

“I think that was the ingenuity of that generation. She used all these American ingredients, but it was all made in a Vietnamese way,” he said.

Along the way, small acts of kindness helped the family survive.

When someone noticed that Tung was taking the bus to get from one job to another, they offered him rides. Later, a sponsor gave him a used car and taught him to drive.

“It was a collective effort, a lot of generous people in the community helped us get through a tough time,” Hong said.

Hong said his parents constantly reminded him and his siblings how lucky they were to be in the land of opportunity and achieve their dreams. The four kids graduated from the University of Michigan and went on to earn graduate degrees. Hong became a doctor, Tam an engineer, Ngoc a public health expert, and Tudo an attorney.

Though he lives far away from his parents, Hong and his wife stay connected to their heritage by speaking Vietnamese to their daughters and by sharing food with their community. They host cooking parties in their backyard to help raise funds for charities. More recently, they made an inventive version of banh mi with brisket and homemade pickles to support victims of the Eaton wildfire in nearby Altadena.

Hong said Tung is 85 and no longer able to speak coherently due to a stroke. Ly takes care of him. Hong said he’s glad he recorded Tung’s memories of miến gà years ago and regrets not doing more recordings while his dad was still able to speak. He said his dad was a great storyteller and had a knack for spotting Vietnam veterans wherever they went.

“He’d approach them really casually and thank them for their service, and next thing you know, they’ll have a long conversation,” Hong said. “He loved to share his stories and listen to other people’s stories as well.”

If his dad could speak, Hong said he would probably say that he’s “forever grateful to America for welcoming us as a family and as a whole community.”

He said he also thinks Tung would be sad about the country’s tough immigration policies under President Donald Trump.

“Part of me also would like to think he would be abhorrent about the current state of America, the freedoms that he escaped and risked his life and lives of his children for, slowly eroding away,” he said.

[ad floatright]

101 episodes

All episodes

×Welcome to Player FM!

Player FM is scanning the web for high-quality podcasts for you to enjoy right now. It's the best podcast app and works on Android, iPhone, and the web. Signup to sync subscriptions across devices.